Day 617 of 1000

This is the ninth in a series of posts on how we taught our children to program, what we did wrong and how we think we could have done better. You can see the introductory post and index to the series by clicking here.

This post describes how I think I would teach an eleven year old kid how to program. I explained the many things we did wrong and the few things we did right in teaching our kids how to program when they were young In the previous posts in this series. We really did not do so badly with our son. He is a good programmer with a solid knowledge of the fundamentals of object oriented programming in C#, C/C++, and Python. His college level Introduction to Java class was a trivial exercise for him. We did horribly with our daughter. So much so that she struggled mightily with the same Introduction to Java class at which our son had excelled.

We have a good (certainly not perfect, but good) track record teaching our kids things like reading, math, art, typing, and all kinds of other stuff, so I have tried to think about what I did wrong and how I might do it if I had it to do over. I think the main reason we did not do so well is that we did not see programming as an essential skill. We were wrong. All STEM majors need to know how to program and that knowledge is a huge advantage to kids who enter a STEM degree in the University.

What language should you chose?

So, what could we have done to teach our kids programming at an early age? There are a lot of small concepts a new programmer has to learn before any attempt is possible to learn the big picture programming ideas, particularly object oriented programming. There are lots of books that explain these details quite well. A language that handles some of the minutiae for the new programmer so they can learn these small concepts one at a time is a big advantage. Languages like C#, Python, and Java all qualify. C/C++ does not for reasons #3 and #4. There are good reasons for selecting one of these languages:

- These are serious languages for serious programmers that can perform anything from small embedded applications for single board computers to game programs running on personal computers to full-blown, big data, internet enabled monster programs running on “big iron”.

- They have large sets of libraries that the new programmer can use without a lot of knowledge about what is going on under the hood.

- Garbage collection (a technical detail we don’t need to go into here) is managed by the language so the new programmer can concentrate on learning the small concepts without the program breaking for mystifying reasons.

- There are very good Integrated Development Environments (IDE) for all of these options. An IDE is a program that is used to write programs. It has an editor, a compiler, a linker–everything need to write, debug, and run a program in an easy to use environment that usually has a hint systems (intelli-sense) for computer commands in case the programmer forgets what he should type next.

- There is a TON of documentation, tutorials, examples, and books on the internet and in print for all these languages.

We started in C# because it meets all the criteria above, I had good knowledge of the language, and we found what looked like a good tutorial book on C# that featured something of interest to my son. That was a great reason to go that direction at the time. I think if I had to do it over, I might start with Python. There is no particular reason that Python would be better than C# or Java, but I am aware of a number of cool, hobby projects written in Python and I would like to get a little deeper knowledge of Python myself.

What book should you chose?

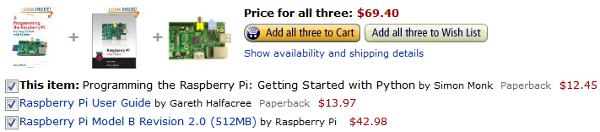

These days, it is possible to get all the information required to program online. I have learned languages that way (Python and R). Nevertheless, for a sit down class with an 11 or 12 year old kid, it is nice to have a book to follow. In addition to the book we used to get started (Beginning C# Programming), I have been looking at a book with great reviews titled Programming the Raspberry Pi, Getting Started with Python. The thing that is great about this book is that, if you already have a USB cable and a reasonably capable PC, you can be complete set up with an embedded computer to write robotic, internet, game, and other kinds of programming for less than $100. Here is the blurb from Amazon for the book, a Rasberry Pi embedded computer, and the Raspberry Pi user manual:

These days, it is possible to get all the information required to program online. I have learned languages that way (Python and R). Nevertheless, for a sit down class with an 11 or 12 year old kid, it is nice to have a book to follow. In addition to the book we used to get started (Beginning C# Programming), I have been looking at a book with great reviews titled Programming the Raspberry Pi, Getting Started with Python. The thing that is great about this book is that, if you already have a USB cable and a reasonably capable PC, you can be complete set up with an embedded computer to write robotic, internet, game, and other kinds of programming for less than $100. Here is the blurb from Amazon for the book, a Rasberry Pi embedded computer, and the Raspberry Pi user manual:

The reason both the books are good is that they start from ground zero, they feature good starting languages as defined above, and they have project goals that are likely to interest kids of the age of 11 or 12. The Raspberry Pi is particularly good because it features a chunk of hardware to which the kids can hook up other stuff and/or connect to the internet. These are just examples, but the concepts behind both these books are great.

How should I do the teaching?

This is an especially good question if you, yourself know nothing about programming. The beauty of the above setup is that the books walk you through the set up of the computer, the download of the language and IDE, etc. They give button push by button push instructions. If you do not know anything about programming, this will teach you. As for your kid, it has been my experience that at 11 or 12, kids generally love to do stuff one-on-one with their parents, even if they sometimes do not admit it. The one-on-one approach is the right way to go. Here were my rules for a structured program like this:

- Go by the book. You might think you have a better idea. You might ACTUALLY have a better idea, but if you stick to the book you will be assured you and your kid have all the materials to go on to the next chapter.

- Sit down with your kid for 20-30 minutes per day, at least four days per week. Be present with him the whole time, but quit after the alloted time so you want to come back for more.

- Let him do ALL the reading. Have him read every word, aloud. Talk about it when you or he don’t get it. Look up explanations on the Internet when needed.

- Sit on your hands. Let your kid hold the book and turn the pages. Let you kid plug in the computer. Let your kid download and install the programs and software. Let your kid do ALL the typing.

That is all I have. I wish I would have done it that way.